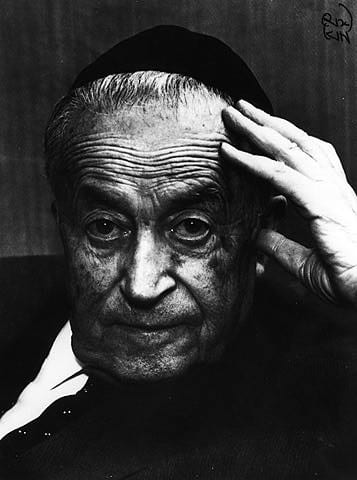

December 10, 1966 – 53 years ago. The clock ticks past 16:00, as the crowd waits in Stockholm’s opulent concert hall for the Nobel Prize winners. The honored guests are waiting anxiously for four stars. Three will herald the end of Shabbat. The fourth is the shining star of Hebrew literature, Shai Agnon.

Soon after Shabbat ends, a posh car pulls up to the Grand Hotel. An elderly couple sits in the back seat in their finest clothes. Agnon, wearing a large black kipah, pulls out an electric shaver to quickly remove a day’s worth of stubble. The woman, Esther nee Marx, glances at her watch and gives her husband a worried look while straightening his collar. “Estherlein, my darling,” Agnon quips smirking to his wife, “I’ve waited for them for so many years. Nothing will happen if they wait a few minutes for me now.”

Irony was a central tool in Agnon’s works. The greatest compositor of Eastern-European Jewish life truly loved his characters. Because of this great love, he did not hesitate to take them down in the thinly-veiled irony emblematic of his writing. They were rounded figures, you know. As in life itself. And as in life itself, Agnon’s journey to the most coveted title in international literature – that of Nobel laureate – was replete with bittersweet irony.

As Dan Laor wrote in his article for Haaretz, “War of the Words: The Intrigues Behind Israel’s First Nobel Prize Win,” Agnon’s anticipated Nobel Prize took decades in coming. The concept was born in the Hebrew press as early as 1938, when “The Bridal Canopy,” an English translation of his Hebrew novel, was published. But for various reasons, at that time the idea did not come to fruition.

The second time was nine years later. Agnon was still in the throes of writing “Shira” when the motion to nominate Agnon for the Nobel was hatched in the halls of the Hebrew University. The architect of that move was Samuel Hugo Bergman, the university’s first president. Bergman enlisted intellectuals in and beyond the university to promote the plan. But to his surprise, when he contacted Professor Josef Klausner – a prominent historian and literary researcher of his day – adamantly objected.

“Agnon is a galuti (Diaspora-minded) writer,” Klausner blasted. “His work never managed to rise to a human height and his main strength is in Galician folklore.” Crazed with envy, Klausner suggested that poet Zalman Schneur was a worthier candidate for a Nobel Prize nomination. The literary researcher didn’t just talk the talk – he walked the walk, enlisting writers and academics to present Schneur’s nomination while Bergman attempted to promote Agnon.

Agnon and Klausner lived at that time a mere 100 meters from each other in Jerusalem’s Talpiot neighborhood. When Agnon heard Klausner’s words, he gave as good as he got. He served his revenge cold. Very cold. Agnon’s monumental novel “Shira,” published 30 years later, featured an entire chapter devoted to a ludicrous professor based on his neighbor and adversary Klausner named “Professor Bachlam.”.Holtzman notes that the chapter titled “At Professor Bachlam’s” is, “Apparently the wickedest and cruelest thing that Agnon ever wrote…a salvo of toxic barbs intended to ridicule every aspect of Klausner’s endeavors – and his personality and manners.”

But in a complete U-turn, the irony backfired first to Agnon’s detriment. In 1958, Klausner passed away and the Jerusalem Municipality’s cultural committee decided to name the street on which he lived in his name. Imagine how Agnon felt passing the street sign bearing his adversary’s name on a daily basis and picking up the letters in his mailbox to see his nemesis’s surname on the front.

The third attempt to nominate Agnon was in 1951. But in what looked like magic, the Schneur camp rose up again to try to thwart the motion. But Agnon’s fan base was bigger this time, and Schneur’s nomination was foiled. In order to increase his chances, Agnon flew quickly to Sweden to meet with influential intellectuals and writers. But the intended blessing turned into a curse. Not only did Agnon endure another disappointment and failure to win the prize, but he suffered a heart attack during the visit and was hospitalized in Stockholm. “It is a great honor that is worth one making a mockery of oneself,” said Agnon on another occasion – and the Nobel Prize seems to be the greatest honor of all.

In 1966, only 15 years later, the longed-for announcement arrived: The Nobel Committee for Literature decided for the first time in history to grant the prize to a Jewish writer who wrote in Hebrew. The Hebrew language waited 2,000 years for the Prince from Buczacz to finally wake her from her slumber with the kiss of his words.

But every rose has a thorn. The sweetness of this victory was tainted with an acrid drop. Agnon actually received half of the whole prize. He was forced to share the glory with German-Jewish poet Nellie Zakas. A genius of literature like him was worthy of keeping the entire prize to himself, but Agnon swallowed the bitter pill. Agnon’s regular readers can’t miss the thinly-veiled but piercing irony in the message to the Nobel committee in his address at the awards ceremony: “Before I conclude my remarks, I will say one more thing. If I have praised myself too much, it is for your sake that I have done so, in order to reassure you for having cast your eyes on me. For myself, I am very small indeed in my own eyes.” The humility is directly proportional to the talent.

Agnon was 78 when he won the Nobel Prize. He went to his final reward in February, 1970, four years later.

(Translated by Varda Spiegel)