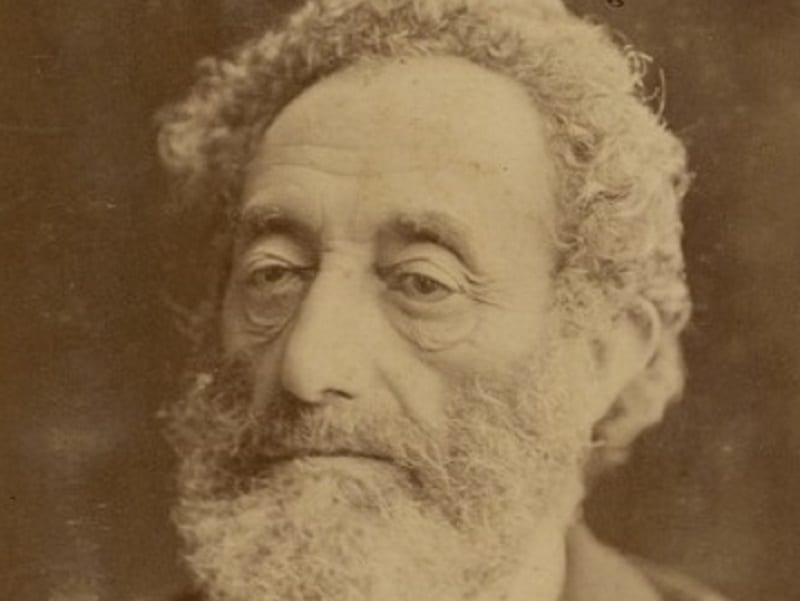

Though he wasn’t the first to publish a modern newspaper in Hebrew; though the paper wasn’t the largest, nor the most popular; though he sometimes copied from his adversaries; and though he didn’t stand out in his education among his colleagues – still, the paper “HaMelitz” and its publisher and editor, Aleksander Zederbaum (“The Cedar”) have a special place in the hall of fame called 19th century Jewish journalism. One of the reasons for HaMelitz’s designation was the city in which it was published – St. Petersburg in Czarist Russia.

When Zederbaum and his partner Aharon Isaac Goldblum launched their new weekly in 1860, they made the obvious choice as for the location – Odessa, which was then the center of Jewish enlightenment. Every eastern European Jew who wished to become part of the literary elite came to Odessa, where numerous groups of authors, poets, and scholars were restlessly writing and publishing, mainly in Hebrew and Yiddish. HaMelitz started in German in Hebrew, and after a year remained exclusively in Hebrew. Then, after ten years, Zederbaum decided it was time for a change – and moved, along with his weekly – to St. Petersburg.

Relocating in the capital of Czarist Russia was not a trivial matter. At that time, most Jews were not allowed to settle in Russian cities and those who were approved had to remain within the pale of settlement, in which Odessa was included, but St. Petersburg was not. Alexander II had relatively liberal views, therefore a few Jews were allowed to live in the capital. But Zederbaum managed to obtain not only the right to settle in the city but also – what was most impressive – to publish his weekly there, under the supervision of the Russian censorship, naturally.

HaMelitz was a fusion of journalistic genres, including general news, stories from Jewish communities around the world, sensational items, intellectual essays, political articles and Hebrew poetry. Zederbaum introduced some important novelties, such as personal editorials in which he shared his views, and also a most controversial method of editing in which he added and published his own comments on items of other writers: mostly critical, sarcastic comments aimed at the writers. Just try to imagine that in today’s press, and you’ll realize unusual it must have been.

The most significant uniqueness of HaMelitz in the Jewish world of eastern Europe was that it was a central platform for a variety of opinions. Zederbaum himself did not conceal his views – after the move to St. Petersburg he came to identify with the Zionist ideology, and supported a national solution for the Jews. Though considered enlightened, he wasn’t identified with the radical parts of the enlightenment movement. Some intellectuals even looked down on him, sensing that his education was limited, his general knowledge was poor, and that he did not speak Russian. Still he insisted as chief editor that HaMelitz should reflect all kinds of views, and gave free hand to writers from all parts of the Jewish society, and encouraged them to debate and argue in the weekly. He also published readers’ responses and comments, sometimes extremely sarcastic, so that the paper would express a wide range of opinions. Thus, HaMelitz has become a main important Jewish voice, more than other papers, who clung to consistent tendencies.

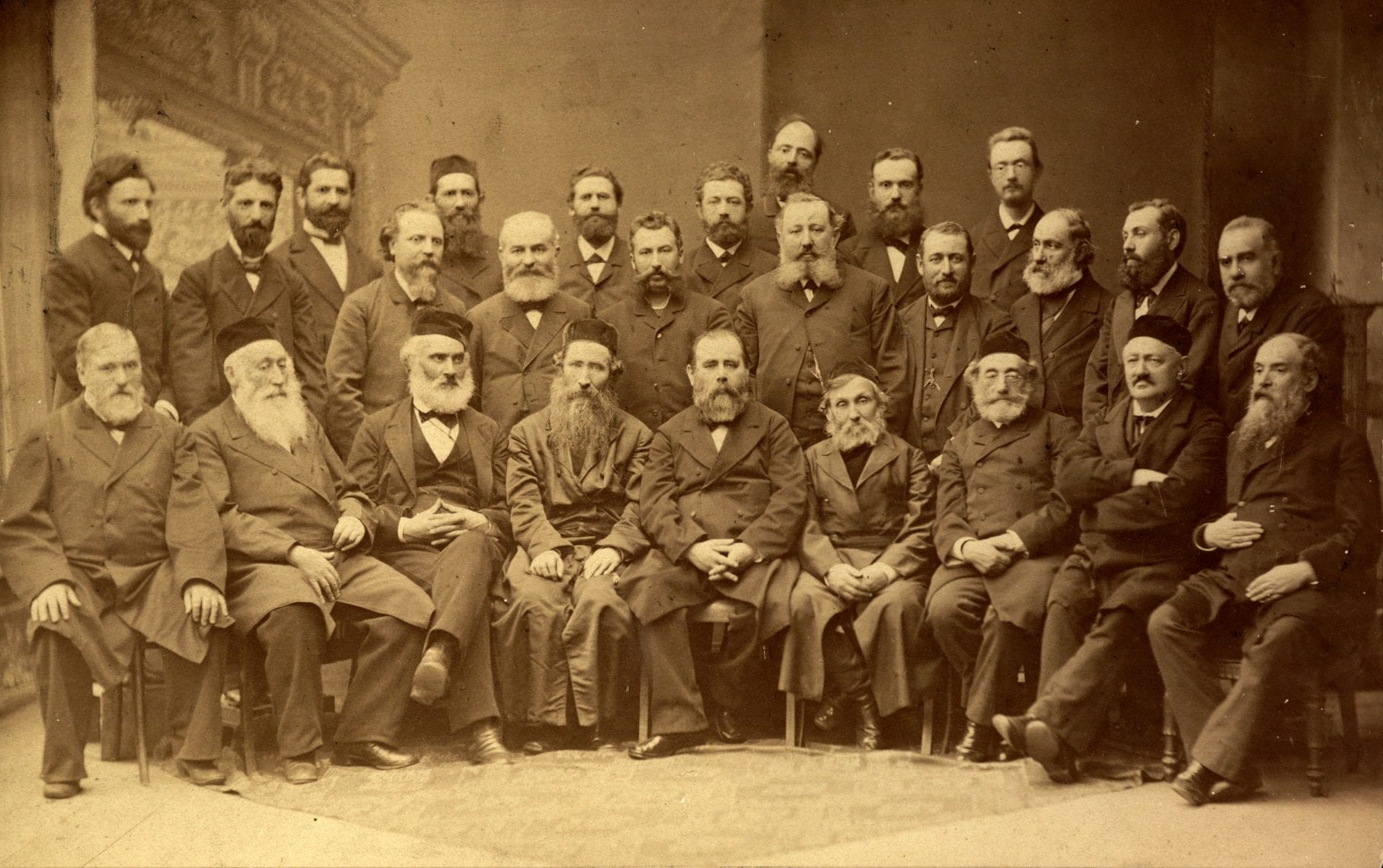

In spite of his insufficient Russian, Zederbaum succeeded in tying excellent contacts with officials and governors in St. Petersburg, probably unlike any other Jew at that time. During the 1880’s, when the first Zionist organization “Hovevei Zion” was being formed, Zederbaum was one of the founders, using his contacts in order to receive the Russian authorities’ approval for its activities. Thanks to his efforts, though under the open eye of the authorities, Hovevei Zion, as well as other Zionist associations that followed, was able to work in the city. Zederbaum participated in the Katowice Conference of 1884, in which Hovevei Zion was formally established.

Zederbaum’s good terms with the city’s officials were not used just around Zionist issues, but also for lobbying for the benefit of the Jewish in Russia in general. In one case, that made him famous among none-Jews as well, he interfered in favor of a few Jews who were falsely accused of murder. Not only did he manage to refute the blood libel, but also confronted Hippolytus Lutostansky, a converted Jew who became an Antisemitic priest. Immediately after the blood libel, Lutostansky begun spreading Antisemitic propaganda in all Russian press, and especially in the capital. Zederbaum published pungent attacks against him in his weekly and in other papers, and even took a risk and announced that Lutostansky was welcome to sue him for defamation – which the latter actually did, and stirred a turmoil in the city. In 1880 the sue was declined by the district court of St. Petersburg and Zederbaum became a local hero not only for the Jews, but for the entire liberal public of the city.

Zederbaum was not the most original editor when it came to his weekly, occasionally coping with competing journals such as “Hatzfira” and “Hayom” by copying their style. He was a charismatic, involved editor, known for his pursue of honor. Yet he was always willing to help the Jews, to promote Zionism and to use the bonds he made in the capital of the Russian empire in favor of others. After his death, in 1893, the popularity of HaMelitz dropped and a decade later it was closed. Zederbaum was buried in St. Petersburg, where he had lived, work and fought his battles for 23 years.