Try to picture this: Shabbat morning, a synagogue in Bnei Brak, and the late rabbi Elazar Shach delivers his sermon to his listeners, in sheer atmosphere of silence and holy awe. Then suddenly, a loud defying horn sound from a nearby sport car is heard just outside the synagogue. Now which scene is more likely to take place?

The driver ends up leaving the neighborhood all beaten up, missing some teeth.

or

Rabbi Shach interrupts his sermon, steps out towards the car and him and the driver embark on a passionate Talmudic “pilpul” (debating), while the rabbi walks the man out of the neighborhood.

If you are even slightly realistic, you probably selected no. 1. But surprisingly, many years ago a situation described in option 2 actually took place. You can read about it in the Jerusalem Talmud, Tractate Ḥagigah, chapter 2.

It happened in Tiberias, on the Shabbat, in the first half of the second century A.C. Rabbi Meir, called in the Talmud “uprooting mountains and grinding them against each other”, was delivering his weekly speech in front of hundreds of followers. Suddenly a hustle. Apparently, a middle aged man arrived at the synagogue court riding a neighing horse. Then, Rabbi Meir ceased preaching, stepped down of his podium and went to the man. They debated over Torah issues, the man still sitting on his horse back, while all the congregation were looking at them with astonishment.

So who was that man, whom everybody expected to be shamefully kicked out of the synagogue for publicly desecrating the Sabbath, but instead received the highest possible honor from the most admired spiritual leader and teacher of his generation? That man was one of the greatest Tanaim, Rabbi Meir’s mentor and instructor, and a friend of Rabbi Akiva. His name was Elisha ben Abuyah, the renowned heretic, known in the Talmud as “other one”.

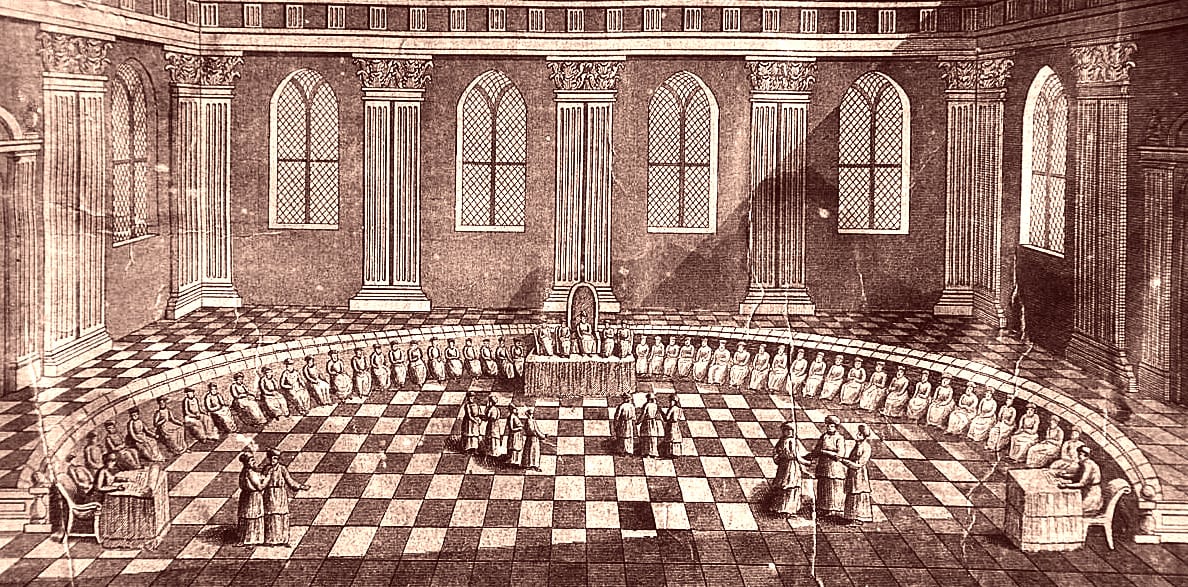

The Talmud praises the wisdom of Ben Abuyah. It is told that while he used to stand and preach Torah in the Hall of Hewn Stones inside the temple, all his disciples and friends used to listen and then come and kiss him on his head. He was included in “Pirkei Avot” – the textual Jewish hall of fame. He wasn’t some reckless wild person, but an influential wise figure, who renounced his faith following a profound spiritual crisis. Elisha Ben Abuyah was the first recorded Jewish heretic, long before other “others” such as Spinoza, Shlomo Maimon, and Uriel da Costa. (We’ll refer to the title “other” hereinafter).

The Gemara in Tractate Ḥagigah includes the story of the pardes (orchard): Four men entered pardes – Ben Azzai, Ben Zoma, Acher (Elisha ben Abuyah), and Rabbi Akiva. Ben Azzai looked and died; Ben Zoma looked and went mad; Acher destroyed the plants; Akiva entered in peace and departed in peace. The pardes is an allegory to the realm of divinity. Accept for rabbi Akiva, all three men paid a high price for entering the pardes. What did Elisha see in the world of divinity, that caused him to perform a religion checkout and exit? In Hagiga 15, it is written that he saw the archangel Metatron (Enoch) sitting on a throne. Elisha knew that up there, no one but the Lord is entitled to sit on a throne, therefore he concluded that there were two authorities rather than one, thus lost his faith.

In Elisha’s time, Gnostic religions came to power. The Gnostic theology is based on a division of the world into two kingdoms: good and evil. Not only in our world does this duality stand, but also in the upper worlds.

All through the Talmud, the character of Elisha is deeply concerned with the issue of evil. If God is omnipotent and gracious, how come there is evil in the world? In one of the Jerusalem Talmud legends, one day Elisha saw a father ordering his child to climb up a tree to perform “Shiluach Haken” commandment (sending away the mother bird from the nest before taking her young). As the boy went down the tree, a snake bit him and he died. Ben Abuyah wondered: the boy filled two important commandments at the same time: “Shiluach Haken” and “Honor thy father”, both are told to prolong the believer’s life, so how come the boy died? And his conclusion was unambiguous: he chose to smash Jewish monotheism altogether.

Interestingly, the sages – Chazal – did not censor the stories about Ben Abuyah. On the contrary, they highly respected him, as the story about Rabbi Meir honoring him at the synagogue implies. That indicated extraordinary openness and acceptance. Even the name they gave him: the other – indicated that his heresy did not derive from personal convenience but rather from deep thinking, from a whole “other” logic and moral perception about the existence of an evil divine force.

“The Other” captured the imagination of Jews throughout the centuries. Among American Jews he even became a cultural icon, as indicated by the success of the novel by Milton Steinberg As a Driven Leaf (1939), which immediately became a must read in every Jewish school in America.

We can only assume why American Jews were so sympathetic with Elisha. Is it possible, that they felt for the “real Jews” who were living in the Land of Israel, they too were considered “other”?