Different estimates show the number of Jews living in the world between 14.4 and 17.5 million – about half in Israel and more than half of the rest in the United States. But the bond to Judaism is not about strength in numbers.Here are five small and distant Jewish communities in the far corners of the Jewish world.

Iquitos, Northern Peru

The city of Iquitos, in northern Peru, is tucked deep in the rain forest. It is the largest city in the world inaccessible by road; people and supplies arrive by air or by boats on treacherous Amazon.

The first Jew to arrive in this remote area was Alfredo Coblentz, who moved from Germany to the nearby town of Yurimaguas in 1880 to work in the Amazon’s booming rubber industry. Five years later, three brothers – Moises, Abraham and Jaime Pinto – moved to Iquitos to work in the rubber field. They only stayed a few years, but others followed. Jews from Morocco soon arrived to try their luck in rubber trading.

Iquitos flourished. Many traders built beautiful homes. One Iquita house, Casa Fierro, was designed by Gustave Eiffel, architect of Eiffel Tower. The Jewish community established a formal board in 1909 and several Jews served as mayors.

In 1948, the vast majority of Iquitos’ Jews emigrated to Israel. Many of those who remained moved to Lima, Peru’s capital, where there is an established Jewish community. Some descendants of the Jewish community remained in Iquitos – often marrying into Catholic families.

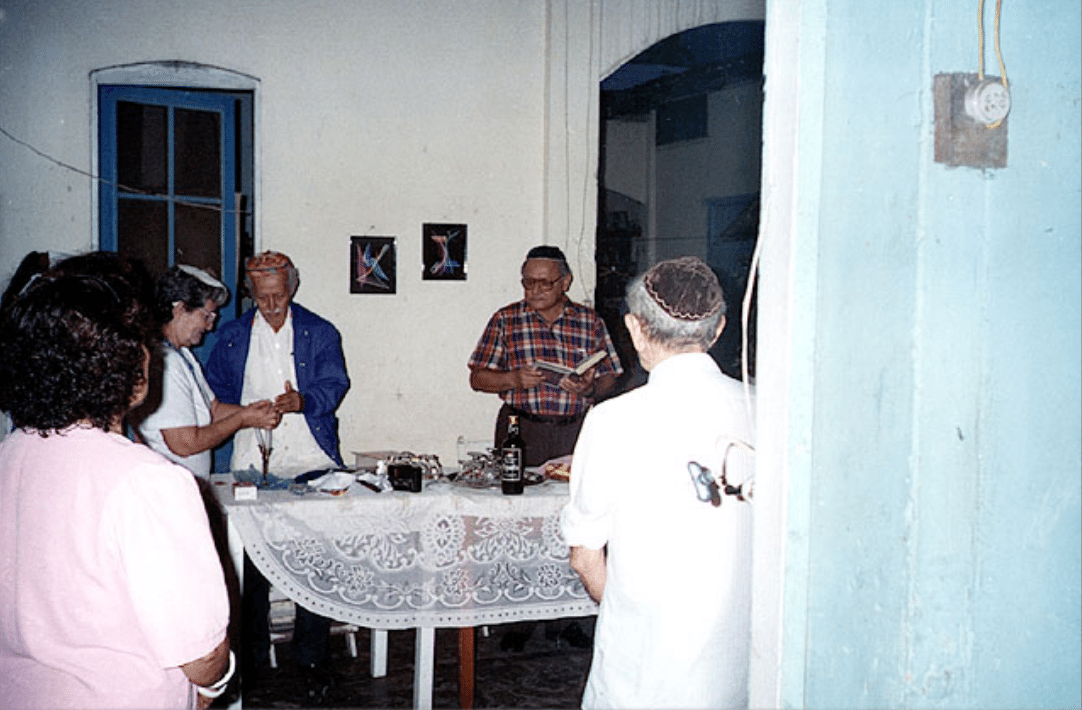

In the 2000s, Jewish leaders began visiting Iquitos, and teaching the few remaining Jews about their heritage. This sparked renewed interest about all things Jewish. Several Iquitos residents with Jewish heritage converted to Judaism and moved to Israel, In particular to Ramla – today, the Jewish-descended community in Iquitos numbers about 70.

Philippines

Jews first arrived in Spanish colony in modern day Philippines in the 1500s – still under the threat of the Inquisition. There are records of trials against Jews practicing their religion from the 1590s.

The next record of Jews in the region is much more recent: 1870, when three Jewish brothers fled to the colony from France to escape the Franco-Prussian War. They soon set up a thriving import business, bringing Swiss watches, early automobiles, perfumes and medicines into the Philippines.

After the Suez Canal was built, the Philippines grew as a trading route between Asia and Europe. One Syrian Jewish businessman, A. N. Hashim, arrived in Manila in 1892 with a suitcase of watches to sell: soon he built a business empire, and eventually built Manila’s Grand Opera House. This small Sephardic community was soon bolstered by American troops fighting the Philippine-American war after the US took over the Philippines as a colony in 1898. Several of the American troops were Jewish, and some decided to stay in the island colony. One notable serviceman who remained was John M. Switzer, a classmate of future President Herbert Hoover at Stanford. He soon built up a canned goods business throughout the Philippines.

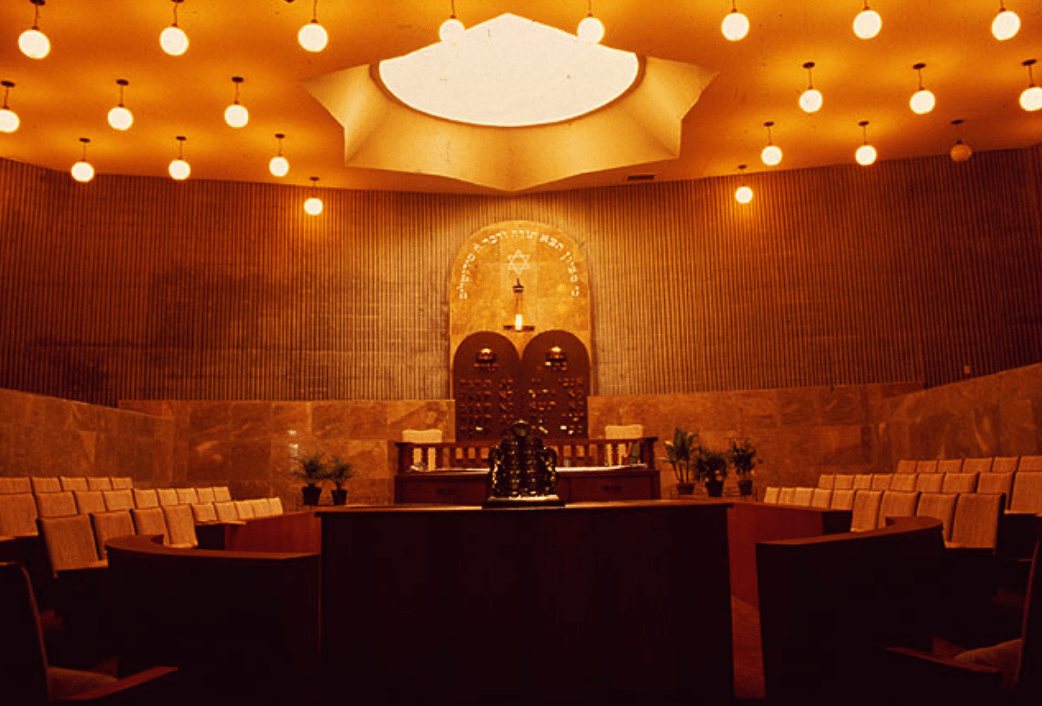

By 1917, the first synagogue was established with a Welfare Board arranged for the importation of kosher food, wine and matzah on Passover.

As Jews faced increasing restrictions and danger in Europe, Manuel Quezon, the first president of the Philippine Commonwealth, tried to come to their help and offered 10,000 visas to Jewish refugees. The United States refused to allow any poor people into the territory, so about 1,200 established European Jews streamed into the islands. They included a rabbi, doctors, chemists, and even a prominent conductor, Herbert Zipper, who went on to found the Manila Symphony.

This haven for Jews was closed in 1941, when Japan occupied the Philippines. Ironically, Japanese forces treated the Jewish refugees better than native Filipinos: seeing the Nazi stamps on Jewish refugees’ passports, it seems the Japanese occupation officials viewed the Jewish refugees as somehow German.

he Philippines was the only Asian country to vote for the establishment of the State of Israel in the UN in 1947. The small Jewish community stabilized at around 300 residents.

Vladivostok, Siberia

Jewish exiles began arriving in Vladivostok at the end of the 19th century, making the city one of a number of places in the far-east that became a home for exiled Jews. In 1897 there were 290 Jews living in Vladivostok (1% of the total population). A synagogue was built in 1916.

In 1926 the community numbered 1,124 (1% of the total population); the city’s development coupled with the growth of the Jewish population in the nearby region of Birobidzhan, resulted in a Jewish population increase at Vladivostok.

In 1932 communist authorities confiscated the city’s synagogue and turned it into a candy factory.

During the Great Terror, which began in 1936, a transit camp was established at Vladivostok for victims of the purge who were sentenced to deportation and hard labor in the gulags. Prisoners, including many Jews, would arrive at Vladivostok by train; from Vladivostok they would be sent to Kolyma by ship.

A Synagogue from 1930’s was reopened in 2015 – due to work by Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia.

Christchurch, New Zealand

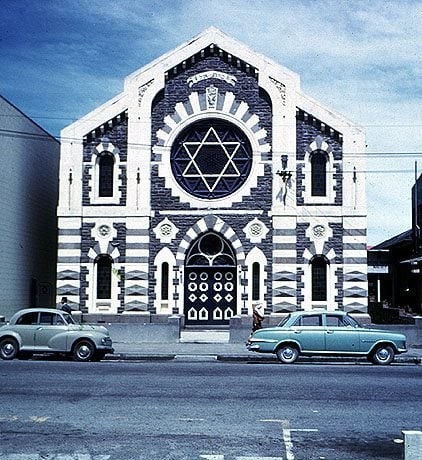

The first Jewish settlers arrived in the South Island Canterbury province in the early 1860’s and under the leadership of Louis Edward Nathan began holding regular services at his home in Christchurch. The moment there was a sufficient number of Jewish settlers in the region, Louis Edward Nathan established the Canterbury Hebrew Congregation, as it did not seem appropriate to include the name Christchurch in the name of a Jewish community. In 1864 the congregation of 30 people obtained a government grant of £300 to build a wooden synagogue in Gloucester Street. The members of the congregation were not affluent, but they wanted to have an organised congregation and paid officials. Despite the fact that it was difficult for them to raise the money needed to pay the reader, his salary was £1.12s. 6d per week.

The exodus caused by a gold rush in another South Island settlement, Hokitika, almost caused the congregation to collapse, but the Jewish diggers and traders returned in 1870, bringing with them their minister Isaac Zachariah, born in Baghdad and educated in Jerusalem, who served the community until 1886. The small size of the Canterbury community meant that members faced a continuous struggle to maintain Jewish education and communal functions and they had to be very understanding about the different levels of observance of one another. In 1885 they decided to read the haftarah in English.

The community flourished under the leadership of Phineas Selig, later doyen of the New Zealand press, assisted by a group of energetic colleagues. Kosher meat was supplied locally from 1933; a welfare society was founded in 1938; a social club in 1940, and women’s synagogue membership was inaugurated in 1942.

According to the 1986 census, there were 129 Jews in Christchurch; however, since then their number has increased and in the 2000s according to the 2001 census and more recent reckonings it was estimated at about 650 Jews in for the entire area of Canterbury, out of a total of 5,500-6,500 for the whole of New Zealand.

Namibia

Namibia has been home to Jews since the mid-1800s. In 1861, Jewish businessmen from Cape Town in South Africa established a trading post along Namibia’s coast, and helped build the region’s copper mining industry.

After Namibia became a German colony in 1884, a number of German Jews helped build up the country: Carl Fuerstenberg, a Jewish banker, helped finance railroads in his country’s newest colony; Emil Rathenau helped form the German South West African Mining Syndicate and funded irrigation projects. In 1917, about 20 Jewish families founded the Windhoek Hebrew Congregation in Windhoek; eight years later, they built a synagogue.

Ironically, while Jew enjoyed safety slowly German forces were testing some practices that would be repeated a generation later in the Holocaust. German soldiers forced Namibia’s indigenous tribes further into the region’s interior desert, and German scientists rushed to Namibia to conduct grisly experiments. Josef Mengele, then a medical school professor, studied Namibians (referring to them as “subhumans”). Heinrich Goering, the father of Hitler’s Vice-Chancellor Hermann Goering, served as Governor of the colony. In 1904, the Kaiser gave orders for genocide, instructing German officials to wipe out the indigenous Herero Tribe. Over 65,000 Herero and other native people were murdered.

South Africa took over Namibia in 1915. Today, only about 90 Jews call Namibia home.

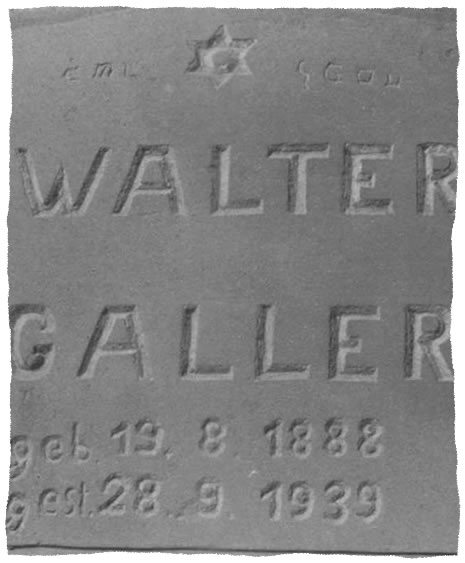

A grave in a remote part of the country emphasizes the difficulties of isolation. A Jew who died apparently asked his family to include some Hebrew writing on his grave. They use the only Hebrew script they could find – his gravestone reads “Here lies Walter Galler, Kosher L’Pesach (Kosher for Passover).” The Hebrew writing is upside down.