On Yom Kippur Minha’s Haftarah, in the synagogue (this year also in yards and balconies all over) it is customary to read a short, somewhat odd story, only 48 verses long, of which the protagonist is one prophet called Jonah.

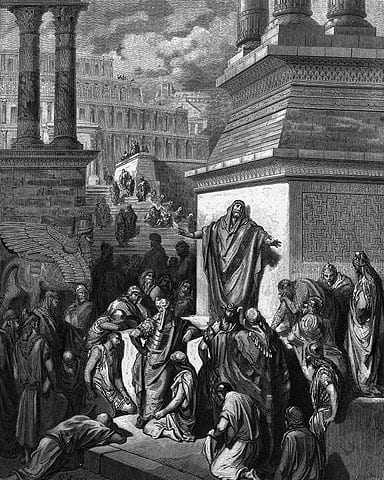

In the beginning of Jonah’s story, he is ordered by God to speak to the residents of the Assyrian capital city of Nineveh, and warn them to correct their evil ways, that included everyday corruption, theft, social splits and moral decay.

Jonah ignores the divine command. As far as he cares, the Nineveh people can go on making each other miserable. He finds a ship in Jaffa and flees to Tarshish, nowadays in southern Turkey, hoping to be left alone there and be dismissed from his mission.

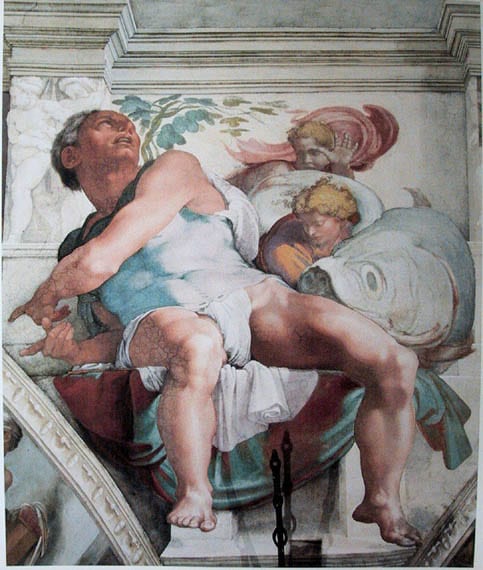

But God does not forget, but rather initiates a storm at sea. The ship’s captain finds Jonah sleeping at the stern, while the frightened sailors throw loads and goods over board, attempting to save the boat. In the midst of chaos and fear, while shouts and cries are heard around, one Hebrew man is sound asleep, completely detached from the situation. The ship-master rebukes the negligent drowsy prophet and tells him off: “What meanest thou, O sleeper? arise, call upon thy God, if so be that God will think upon us, that we perish not.” (Jonah 1,6).

At the eye of the storm the sailors decide to cast lots in order to decide who was responsible for the storm, and blame it on Jonah. He tells them that he is of the Hebrews, escaping his Lord, whom he fears. The sailors consult with Jonah what should they do with him and he asks them to throw him over board, as he’d rather die, than not perform his obligatory mission.

The foreign sailors, characterized as illiterate and common, refuse to perform such a hasty, horrible murder, and do their best to save Jonah: “Nevertheless the men rowed hard to bring it to the land; but they could not: for the sea wrought, and was tempestuous against them. Wherefore they cried unto the Lord, and said, We beseech thee, O Lord, we beseech thee, let us not perish for this man’s life, and lay not upon us innocent blood: for thou, O Lord, hast done as it pleased thee.”

The seamen plead to God not to force them to become murderers, and even while throwing him to sea they only dip him half way. Then, Chazal say, the sea at once became quiet, therefore they pulled him back on board, and the sea stormed again. Only then did they dip him fully. Even though they knew that Jonah’s presence on the ship risked their lives, the pagans fought for the life of a random Hebrew indifferent passenger, and threw him only when they were out of any other options. But why?

Why did the narrator of such a concise story go out of his way highlighting the humane efforts of the foreign seamen? The reason lies in Jonah’s reservations of his mission in the first place – and is closely associated with the deep essence of Yom Kippur.

Obsessed with text compactness, the biblical narrator offers us a clue in Jonah’s last chapter, where Jonah says: “for I knew that thou art a gracious God, and merciful, slow to anger, and of great kindness, and repentest thee of the evil.”

Jonah fears that following his preaching, the people of Nineveh will repent, after which God will be merciful and withdraw from his plans to burn down the city. Why is it a bad development? Why shouldn’t repented people be pardoned? The answer lies in 2 Kings, 14, 25, where we are told of the second Jeroboam King of Israel, who “restored the coast of Israel from the entering of Hamath unto the sea of the plain, according to the word of the Lord God of Israel, which he spake by the hand of his servant Jonah, the son of Amittai, the prophet, which was of Gathhepher.”

Living in a time when Jeroboam expanded the kingdom’s border until it bordered with Assyria in the north, Jonah feared that Assyria might threat his beloved kingdom of Israel. Therefore, when was pleased to learn that Nineveh was about to be punished, as he hoped that Israel will benefit from Neneveh’s destruction. Then he got worried lest the “merciful, slow to anger” shall regret his plans and Israel shall then be harmed and defeated.

Which is exactly what actually happened. A great fish swallows Jonah, then vomits him out upon the dry land after three days. Finally, Jonah realizes he cannot escape his mission, and carries on to Nineveh to speak out his prophecy. His fears come true, the people repent and get pardoned by the Lord.

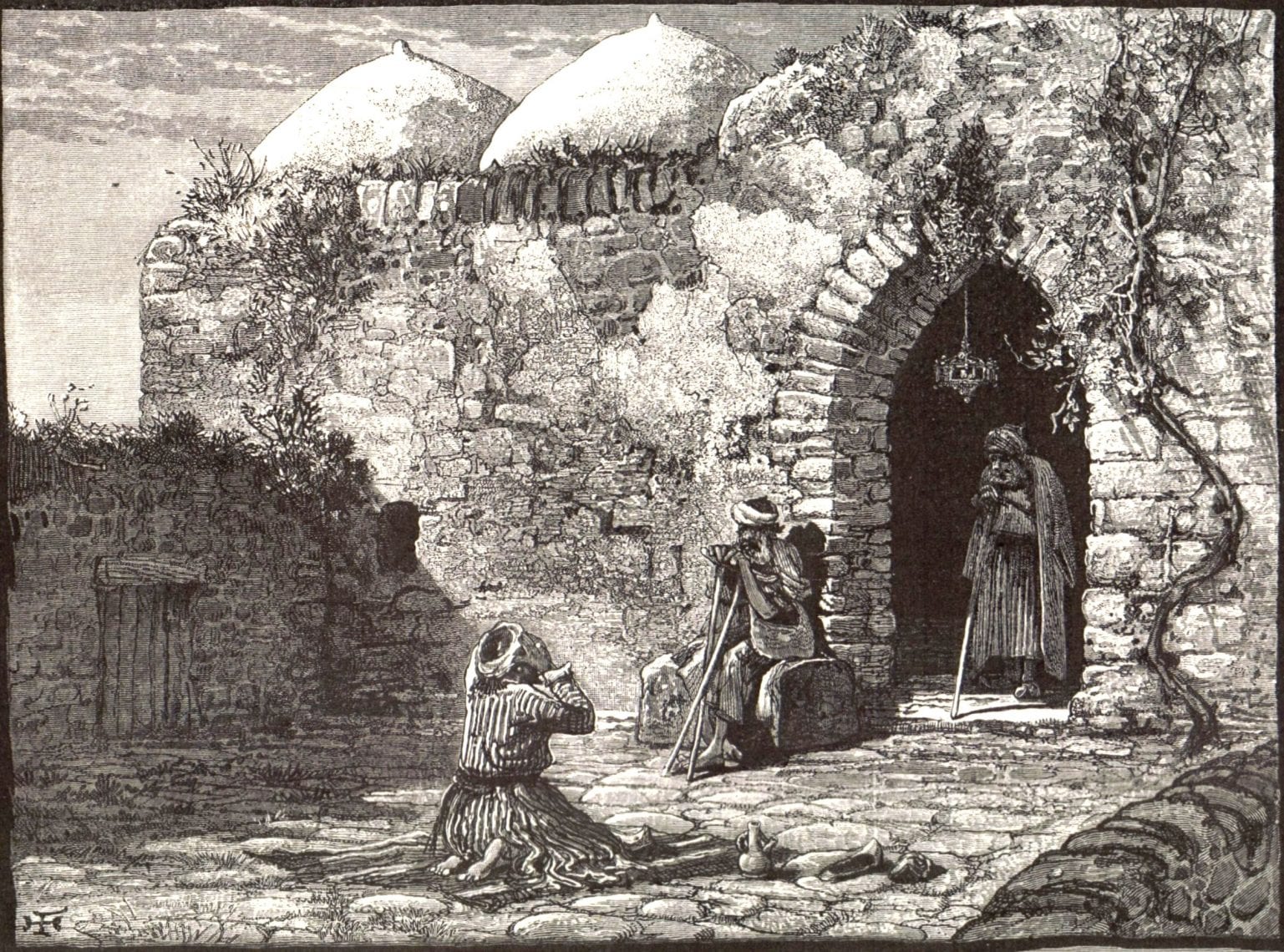

As his hopes for to the elimination of Nineveh shutter, melancholy overcomes Jonah, he builds a shack outside the Assyrian capital and awaits his death under the harsh sun. God provided him with a gourd to shade over him, but a worm comes at night and eats the plant. Depressed, Jonah wishes to die. Then the Lord says: “Thou hast had pity on the gourd, for the which thou hast not laboured, neither madest it grow; which came up in a night, and perished in a night: And should not I spare Nineveh, that great city, wherein are more than sixscore thousand persons that cannot discern between their right hand and their left hand; and also much cattle?”

God’s compassion for potential enemies of Israel; the repent of the people of Nineveh; and the grace of the seamen – the purpose of all of these in the story is to teach Jonah a lesson: when a choice has to be made between the personal and the national or tribal – the story chooses the personal.

This is why, we feel, the book of Jonah is read on Yom Kippur.

Though part of the national circle of holidays, the real meaning of Yom Kippur is humanity. Yom Kippur is about the sole examination of one’s self, separated from religious or ethnic attribution. The individual is judged by their actions alone.

A world pandemic that attacks each and every one, regardless of religion or nationality, certainly reminds us this important lesson.

(Translated from Hebrew by Danna Paz Prins)